The June 2015 mass shooting in Charleston, South Carolina was tragic, yet predictable. 21-year-old Dylann Roof entered the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in downtown Charleston and opened fire with the intent to start a “race war.” Five times he reloaded his .45 caliber pistol—received legally as a birthday gift from his father despite his pending felony drug charges. He finally turned the gun on himself, only to find it was empty. In the end, nine church members were killed. Roof was later arrested and is awaiting trial.

As often occurs, the focus in the days that followed shifted toward more symbolic matters. Mass protests led South Carolina to remove the flag of the Confederate Navy—commonly referred to as the “Confederate Flag”— from its statehouse. Major retailers followed suit, pulling items featuring the Southern Cross from inventory.

Yet, many of those same retailers still sell firearms in their stores. A prime opportunity to start a proper debate on gun control quickly diluted into ill-informed Facebook posts about the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Firearm Laws in Japan

The most common “middle-ground” argument for gun control in the U.S. is to restrict ownership of military- and police-style automatic and semi-automatic guns. In Japan, it’s illegal for citizens to own handguns, automatic assault weapons, semi-automatic assault weapons, military rifles or machine guns. Even possession of a sword without a permit has been banned since the end of the Samurai era.

The only firearms Japanese citizens may own are rifles for hunting or sport shooting use. Before attaining a license, they’re required to take written and practical exams, receive a mental health evaluation at a local hospital and be screened for drug use. If they pass this first round, the police begin background checks, interviewing family members and looking into personal and political affiliations. Certain memberships lead to automatic refusal of the license.

The license is valid for three years, at which point the exams must be retaken to renew the license. During the three years, owners are required by law to keep the gun and ammunition in separate locked safes and provide police with a detailed map to the location of the safes in the home. The firearms are inspected annually by authorities.

In the case of an unlicensed firearm discharge, there are actually three separate crimes being committed. The possession of the gun is a crime, subject to a 10-year prison sentence. The discharge of the weapon is obviously another crime, but it’s also illegal to possess the bullet. As a result, even the Yakuza (Japanese organized crime) tend to avoid guns.

Even better, guns are not considered family heirlooms. Upon the death of a gun owner, the firearm is required to be turned into police. They cannot be simply transferred between family members, something that might have prevented the Charleston shooter from becoming the owner of a pistol.

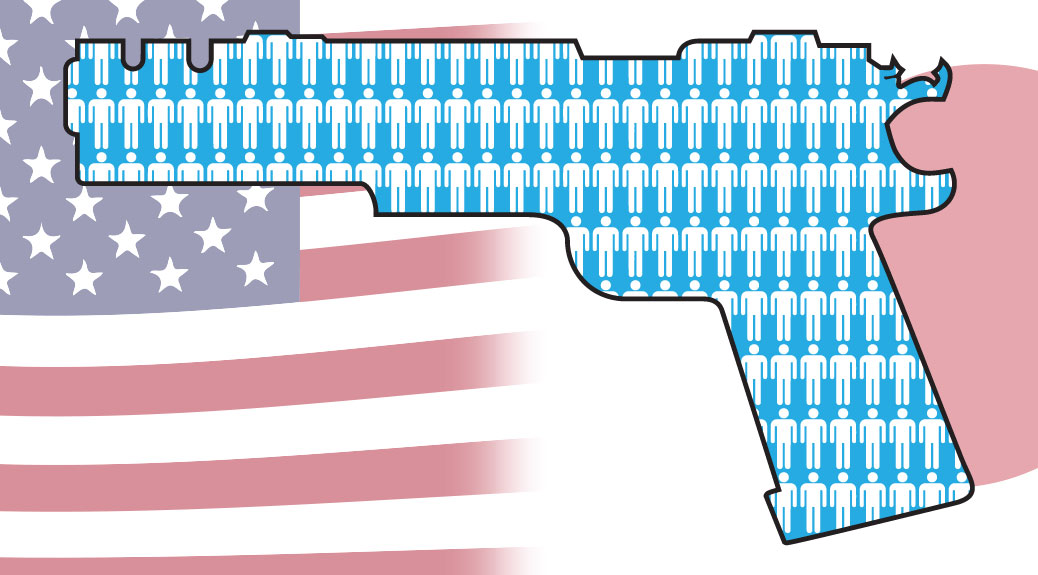

This restrictive approach to gun control have led to a very low rate of gun ownership. For every 100 people in Japan, less than one firearm is owned compared to 88.8 guns per 100 Americans. Firearm sales in the U.S. is one of the few industries that not only weathered the recent recession but experienced growth.

By The Numbers

So, do these tight gun controls make a difference? Absolutely.

In 2006, the U.S. had 10,225 firearm-related homicides. Japan had two. Seriously. Two. The following year, that number skyrocketed to 22 and it was treated like a national crisis. Since 2007, the number of total gun-related murders hasn’t topped 19.

Total homicides isn’t a great measure since the U.S. outnumbers Japan by 195 million in total population. Comparing homicides per 100,000 people in the population levels the playing field. The U.S. hovers around 3.5 to 4 homicides per 100,000. Japan is below 0.02 homicides per 100,000.

Heck, more people accidentally shoot and kill themselves in the U.S. than total firearm related deaths or injuries in Japan in any given year. In 2013, the U.S. had 505 accidental gun deaths. From 2009-2013, Japan had 182 firearm deaths TOTAL—accidental or otherwise.

The Culture Gap

In the U.S., the Constitution is wielded irresponsibly by the average citizen, not unlike so many of the aforementioned firearms. In the case of firearm ownership, the Second Amendment is the rope in the eternal gun control tug-of-war.

At worst, the Second Amendment is an argument for the proper use of commas. It reads:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

For the individual rights folks, it’s crystal clear that their rights shall not be infringed. For the collective rights backers, it’s crystal clear that this is intended for Militias, not individuals. So, who’s right?

Everyone!

In reality, the original intent of the Second Amendment was likely to allow private ownership of firearms to keep local militias from getting out of control in the years following the founding of the nation. Over time, that need dissipated as the military centralized. In 1939, the Supreme Court adopted a collective-rights precedent in a case regarding the transfer of sawed-off shotguns. The Court followed this precedent until 2008 when it ruled that the 30-year old handgun ban in Washington D.C. violated the Second Amendment. They’ve continued to make rulings with this later interpretation in the years that followed.

Note: While total gun-related homicides are down in D.C. since 2008, it still leads the nation in deaths per 100,000.

The “individual rights” mindset is why it will be an uphill battle to expand gun control in the U.S. Many arguments go something like “The criminals have guns, so I need a gun to protect myself and my family.” It’s literally an individual arms race that’s growing like Cold War-era nuclear proliferation. Few are willing to give up their individual rights, even if it means a better nation overall (see the Affordable Health Care for America Act, i.e. Obamacare).

Yet, will responsible gun owners ever be willing to compromise for the good of the whole? Hunters and sport shooters don’t need to give up their rifles, but will they hand in their semi-automatic hand gun if other, less responsible owners will do the same? It seems this group may need to be willing to take the lead for real change to occur.

In Japan, the national identity is far more collective than in the U.S. The lack of access to firearms has zero impact on personal security. This is a conscious choice made by the society. The strong sense of individual responsibility leads to a collective national responsibility—each person takes care of themselves as a part of taking care of the whole. Each person also chooses to sacrifice a bit of themselves for the betterment of society.

Interestingly, the most significant foreign effort toward gun reform in the U.S. comes from Japan. Every year, petitions containing hundreds of thousands of signatures are sent to the U.S. government.

The effort began in earnest. In 1992, a Japanese exchange student in Louisiana was shot and killed by a homeowner after he accidentally entered the wrong home on his way to a Halloween party. He didn’t understand the English idiom “Freeze!” meant that he needed to stop. While only a blip in the U.S. news cycle, the outrage that followed in Japan has carried on to this day.

Hope For Change

It may seem impossible that the U.S. could implement a system like Japan’s. Aside from the sheer collection of unauthorized firearms and licensing protocol changes, the real challenge is changing public opinion enough to turn the tide toward real reform. But consider this:

In 1996, gun massacres in Australia—similar to those in the U.S. today—were on the rise. A “pathetic social misfit” opened fire in a popular Tasmania tourist location, killing 20 people in 90 seconds with a semi-automatic military-style rifle. When the literal smoke cleared, 35 were dead and 18 more were injured.

Then-Prime Minister John Howard announced a major reform to Australia’s national gun laws, working with each of the country’s states and territories to enact widespread change. Automatic weapons were banned. Licensing requirements were tightened up and personally-owned firearms were licensed.

In two separate federally-funded buy-back programs (paid for by a one-time tax on all Aussies), the government collected and destroyed more than 1 million firearms. New imports of automatic and semiautomatic weapons were banned.

In the years since, the rate of firearm-related deaths—both murders and suicides—plummeted more than 50 percent. Even the most recent event, the cafe shootings in Sydney, only resulted in three deaths, including the gunman.

The Australia action was successful because of strong leadership at the top of government, a willingness for individual states to sacrifice for the greater good and a wave of support from Australians to see changes made to save the lives of their fellow citizens. Rural politicians took hits in the following election, but it worked.

Will America be willing to create this wave required for change? Will we heed the words that preceded not only the Second Amendment, but created the foundation for our country?

We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Only time will tell.

Robert, pessimist that I am, I doubt I’ll live to see the day we follow Australia’s example. But then, I never thought I’d see the Berlin Wall come down either.

Like I said, it’s going to take a MAJOR cultural shift and leadership from the gun-toting community for change to happen. I’m pretty optimistic generally, but this one’s a tough one to see happening in my lifetime either. Here’s hoping!