We stepped off the boat, climbed a steep set of crumbling stone steps and entered the city’s dark back alleyways. The always-fragile electricity failed and everything went pure black. A few long seconds passed before the lights flickered back to life. Re-illuminated, several men carried yet another dead body past us, chanting “Ram Nam Satya Hai”… The name of God is truth

We followed one of the boat’s crewmen toward the center of the market, the narrow alleys filled with eager shopkeepers trying to get your attention. A motorbike pushes through the crowd. We get stuck between a group of people—faces marked with colored powder—and a large bull. Whispers of “Hasish?” come from the shadows, preying on those looking for an additional perk on their spiritual journey.

It sounds like a scene from a thriller movie, but this was very much real life. Welcome to Varanasi, India—the world’s oldest city.

A City of Death

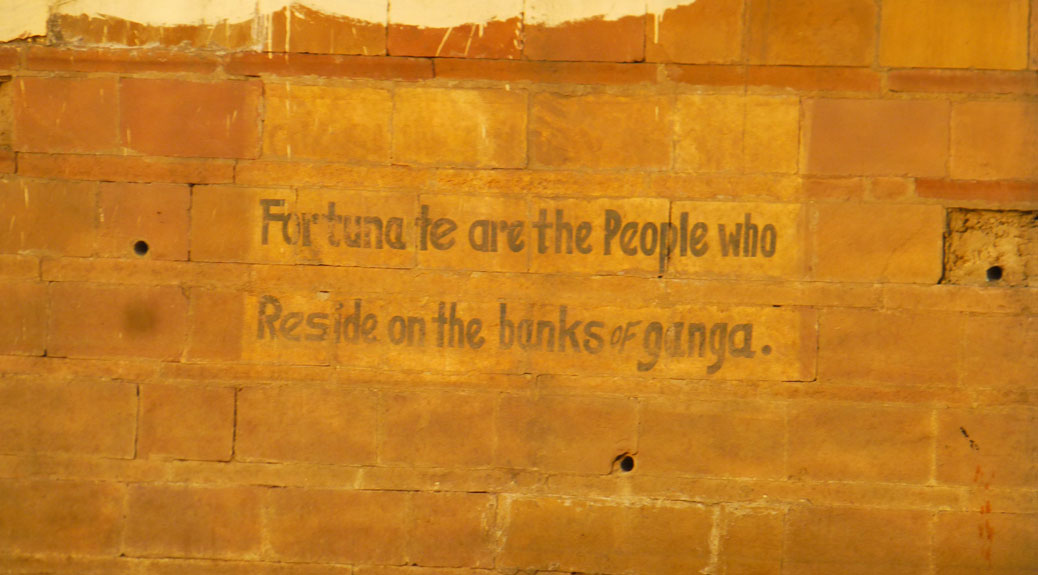

Varanasi is one of Hinduism’s three holy cities along the Ganges River. When a Hindu person dies, the family will transport the body to one of these cities for cremation and the ashes will be brushed into the Ganges. Hindu’s believe in reincarnation and that placing the ashes in the river will allow the soul to escape the cycle of reincarnation, setting the spirit free to move into the afterlife.

In most Western countries, death is something to be hidden away. But in India, it’s very much a public affair. After a preparation period in the home, the body is transported to the city. The body is wrapped in a shroud—most that we saw were gold in color—and carried through the streets to the ghats alongside the river. The eldest son is in charge of the preparations and leads the processional.

Our tour guide gave us the option of visiting Varanasi’s famous ghats (stone staircases leading down to the Ganges) to view the cremations, which take place all day, everyday. I’m glad to have seen it as it offered an important look into the country’s culture, but it’s not something that you can really prepare to see. It’s simultaneously beautiful and disturbing.

Out of respect to the grieving families, we were requested not to take photographs—and I believe human decency dictates this as well. The body is laid upon a wooden funeral pyre and covered in clarified butter (ghee), which is both a cleansing ritual and a practical method to help the body burn. The eldest son—who has shaved his head in a sign of respect to the deceased parent—lights the fire and performs rituals. He stays with the body until the fire has burned out. The ashes are brushed into the river and several more days of ritual follow.

I can remember vividly the sight of the body on the pyre. My stomach soured and clenched with the feeling of seeing something you shouldn’t see. The top of the head and the bottom of the feet were visible, reminding you that a person is inside the blazing fire.

A City of Life

As you move away from the Ganges, the city comes to life. Like most of India, tourism is a critical part of Varanasi’s economy with more than 3.2 million visitors—mostly Hindu pilgrims—coming through the city every year.

The first permanent settlements in the area date to the 12th century B.C. You can feel the history as you get lost in the narrow alleys packed with shops and food stalls. Varanasi grew in importance in the 6th century B.C. thanks to a burgeoning silk manufacturing industry, an enterprise that is still the city’s dominant industry 2,500 years later.

Our tour leader took us to one of the silk shops. Not unlike a carnival barker, the show is part of the sales experience. They bring out piles of beautiful, colorful fabrics. Your uneducated hands and eyes try to decipher which is rayon and which is silk, but guess completely wrong (hint: both scarves are rayon!). Burning the thread is the only way to tell the difference (silk singes like hair, rayon melts like plastic).

They pull out the silk and the cashmere and the really-nice cashmere, known as pashmina. Pashmina comes specifically from the inner wool of high-altitude Pashmina goats who shed their thick winter coats every spring.

On our free day, we wandered the streets and eventually were befriended by a local shopkeeper. He gave us the nickel tour of the lesser-known sites along with his myriad of opinions on the state of the city and India as a whole. Along the way, we passed a barber shop set up in a tiny alcove in one of the alleyways. I mentioned wanting to get my beard trimmed and he offered to help orchestrate the transaction.

Granted, I don’t have many hairs left to trim, but the barber did a nice job, polishing off the experience with a variety of face creams and a post-trim face massage. When he finished, I asked our new friend how much I owed the barber. They bickered back and forth for a bit… the barber said the haircut was 25 rupees, but because I was a tourist, he felt like he could charge 50 rupees.

We encountered this many times along the way in what I considered to be a “win-win-win” situation. The barber feels like he can get double his regular fee because I’m a tourist. His “double” fee is about 80 cents USD, so I win because I just got a haircut for less than a buck. He wins because I think an 80 cent haircut is ridiculous and give him 100 rupees (because a $1.60 haircut is somehow not ridiculous).

- He wins.

- I win.

- Everybody wins!

Animal House

A little animal fun…

Mornings in Varanasi

And finally, the peaceful side of Varanasi can be found at 6 a.m.

What a fabulous experience for you folks. So happy for you.