One of my earliest childhood memories is of sitting in the kitchen with my mom. I remember asking “Why doesn’t everyone speak English?” It made perfect sense in my little head. Everyone must translate it into English in their brains to understand it, so why don’t they just say it in English to begin with?

I don’t remember the exact answer, but Mom explained how people speak different languages and they might translate our English into their own languages to help them understand. It certainly framed my perspective in life.

A hot button issue in the U.S. immigration debate is whether or not foreigners should have English-language proficiency before they’re able to become permanent residents. Pew Research Center projects that 82% of population growth in the U.S. between 2005 and 2050 will be immigrants and their descendants. I can imagine at some point in the future, the debate will extend to whether all Americans should be bilingual in English and Spanish.

Over the years, I’ve always fell on the side of “live and let live” when it comes to language. But when we made the decision to move to Japan, I knew that I wanted to learn Japanese, much in the way that I suspect most immigrants to the U.S. want to learn English. However, learning a new language isn’t something that just happens. I have two years of high-school Japanese under my belt, which has helped me some, but even that isn’t enough for me to be able to communicate my needs. If Japan had proficiency laws, they wouldn’t let me within a million miles of the shoreline.

I found that we’ve approached learning Japanese in line with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. We started with vocabulary and phrases related to food. I would like… Do you have… Does it have meat or fish… Now that we’re able to sustain ourselves, we’ve been able to start adding some additional words and phrases to enhance our experiences.

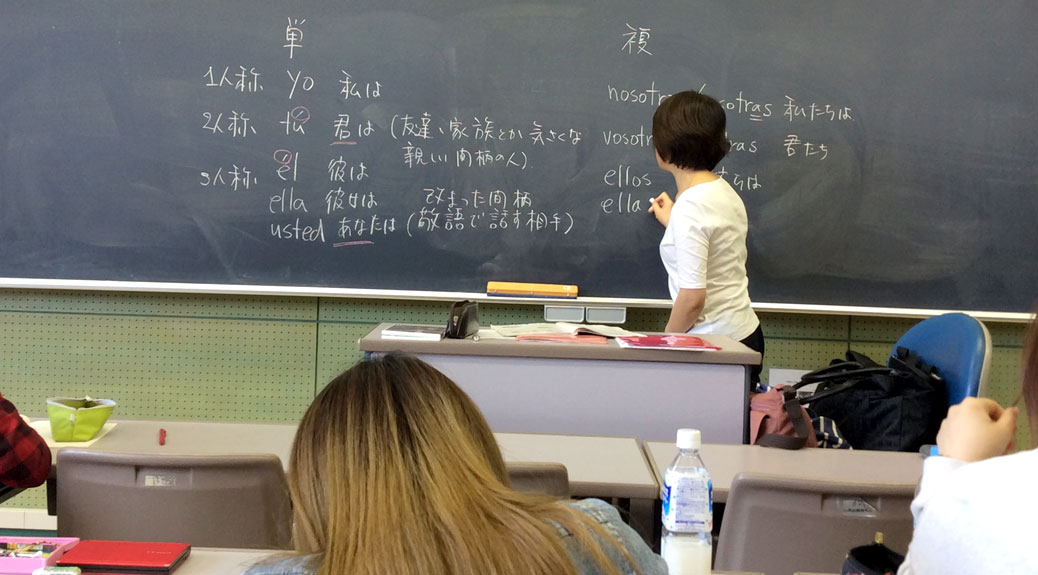

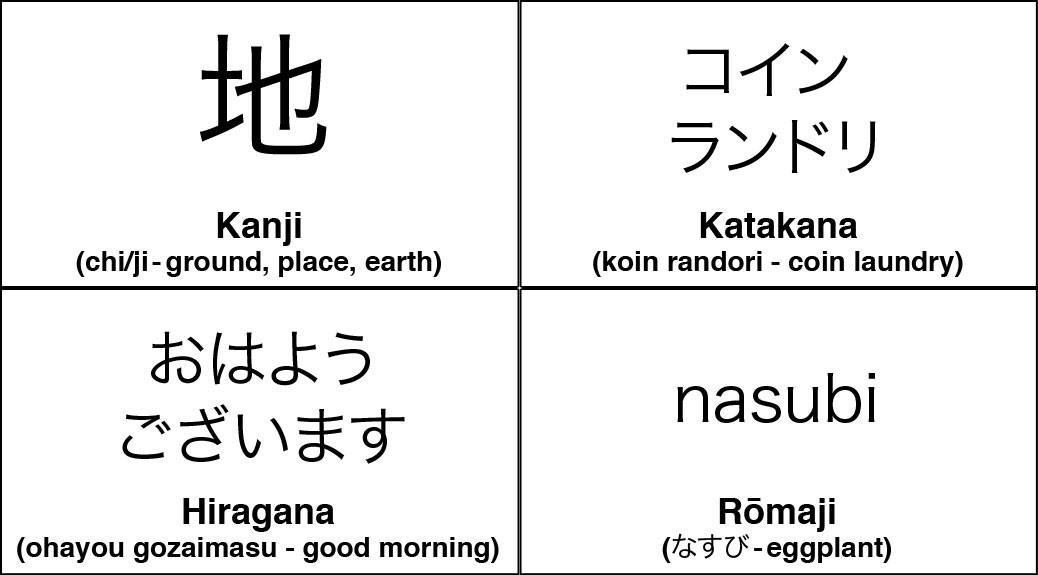

Reading and writing is critical as well. Navigating the trains and stores require the ability to read. Japanese has four primary methods of writing.

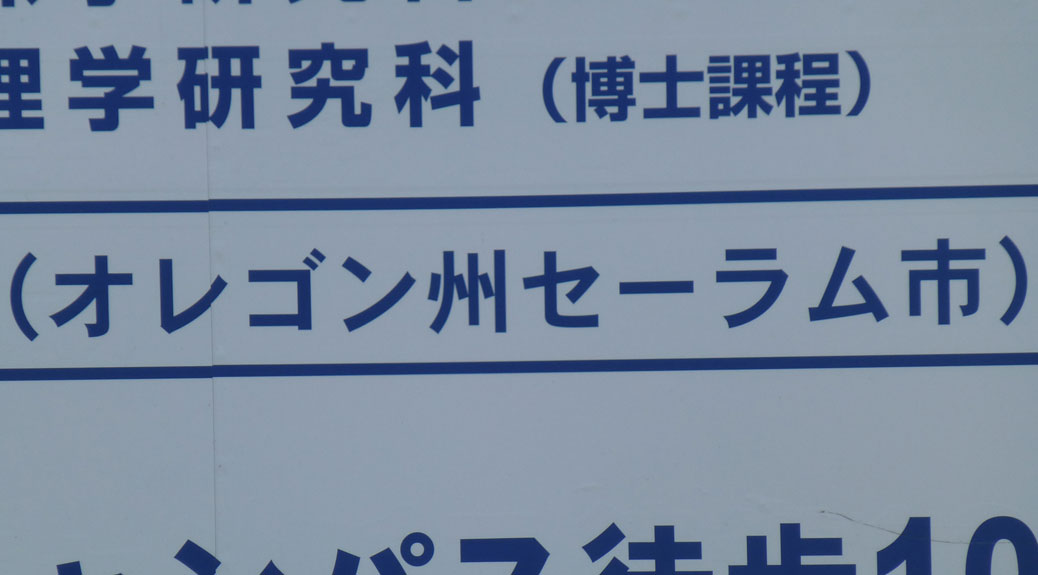

Kanji is adapted from Chinese and each symbol typically represents a word or words. Depending on how they’re combined, they take on different meanings. Elementary school children learn approximately 1,000 kanji and some estimates have the total number of kanji somewhere around 50,000.

Hiragana is used as particles to connect kanji, but also to spell native Japanese words for which no kanji exists. Katakana is used primarily for foreign words. It has mostly the same sounds as hiragana, but is a different character set. Finally, rōmaji is used to help non-Japanese readers navigate the Japanese world. For example, most street names, government documents intended for foreigners and advertisements use rōmaji heavily.

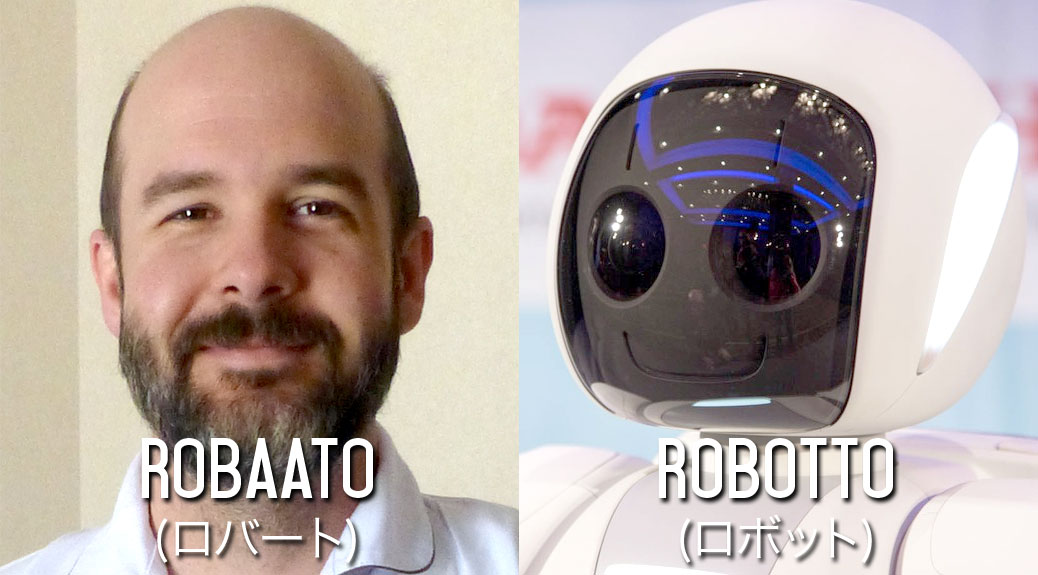

In theory, Japanese should be easier to learn than English. The Japanese language has five vowel sounds and 17 consonant sounds vs. the 20 vowel sounds and 24 consonant sounds in English. For example, in Japanese, the “a” vowel is always an “ah” sound (ka, ga, wa, etc.). But in English, the “a” vowel can be long, as in “ape,” short as in “apple,” an “uh” sound like in “zebra,” an “ah” sound like in “art” or in the case of “orange,” the darn thing just disappears completely.

Learning Japanese hasn’t come without more than its fair share of frustrations. As one of our friends put it the other day, it has a “one step forward, two steps back” feel about it most days. I feel confident at restaurants and grocery stores, but if the neighbor drops by or a salesman comes to the door, it’s like starting from scratch.

The hardest part for me has been the frustration of not being able to communicate. I like to make small talk with the store clerk or people in line. I tried to make a comment about the weather at the grocery store the other day. I was buying a new umbrella and said Ame, desu ne! which was my best shot at It’s really raining, isn’t it? The clerk laughed and replied with a long string of words I didn’t know. Since she laughed, I laughed too, which encouraged her to continue. I faked it as best I could, but I’m sure she sensed the conversation was one-sided from that point forward.

It’s only been three months, so I know I have to cut myself some slack. I’m picking up more and more each day and am starting to figure out some tricks for retaining what I learn. I’ve been making up little songs when I learn something new, which helps the phrase stick. My reading of hiragana and katakana is probably 95 percent, which means I can usually figure out the other 5 percent. I haven’t spent much time with kanji, other than memorizing things like “meat’ (肉) and “fish” (魚), but I’m starting to recognize common ones, like “river” (川), “entrance” (入口), “exit” (出口) and “mountain” (山).

Lately, I’ve been trying to focus on grammar. I figure if I can pick out the pieces of language, that’s when you really start building a toolbox. You can start to construct new ideas and, even if not 100 percent grammatically correct, there is at least some meaning to the listener.

Even in high school, I never really tried to learn a language. My only point of comparison is learning programming languages. With those, there’s always the initial struggle followed by the belief that you’ll never learn it. Then, one day, something clicks and all of a sudden you’re proficient. After awhile, you start to have dreams in code (which can be a great way to solve a problem that you’ve been chewing on all day).

I don’t think I’ll be fluent in two years. Heck, I’m not even sure if I’ll be able to carry on a conversation. But, I think I’m off to a good start and maybe someday I’ll even have a dream in Japanese. I have a real motivation to learn, not just to survive, but to thrive.