Look at Jordan on a map and you might not think “tourist destination.” Bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Israel and Palestine to the west, Jordan is the calm eye in the center of the Middle East storm. And its capital city of Amman is full of surprises.

Amman is one of the Arab world’s most westernized countries, taking influences from each of its various conquerers. The first evidence of civilization dates back to 7600 B.C. and the settlement of Ain Ghazal. In the 3rd century B.C., the Greeks renamed the city Philadelphia. The Roman Empire arrived a couple hundred years later, leaving remnants behind that stand as tourist sites today. In the 7th century A.D., the Rashidun Caliphate introduced Islam. The Ammonites gave the city its modern name in the 13th century. The Ottomans followed in the 16th century and spent the next 400 years laying the foundation for modern Jordan.

Jordan and Amman surprised us, starting with Queen Alia International Airport, located about 20 miles south of central Amman. The clean, modern airport with short lines and polite customs agents was a welcome departure from the chaos of Cairo International Airport. Our driver waited patiently near the entrance with our name on a card to take us to the city center. A Muslim man performed ritual foot washing in the men’s restroom sink.

By late afternoon, we’d arrived in the lively city center and immediately set out for sightseeing before sunset. Amman is built into 19 hills, which offer several unique and breathtaking views of the city. Atop one of those hills is Amman Citadel where the aforementioned history of Amman is on full display.

From the commercial center of King Faisal Street, the road to the Citadel is a series of switchbacks up the side of a hill. On foot, we found ourselves winding between homes, accidentally ending up on someone’s back porch along the way. Struggling to find the entrance, a local suggested we climb a short stone wall and go up the side of the hill. After a couple attempts that resulted in a full blowout of an old pair of pants, we thanked him for his advice and found an alternate path to the top.

Once inside, we were met by only a handful of tourists wandering the grounds. The jewel of the Citadel is the Temple of Hercules. Visible from various points in the city, the 33-foot tall Roman columns glowed gold in the afternoon sun. Built around 160 A.D., it’s believed that the final structure would have resembled the Pantheon in Rome. Today it has more in common with the ruins of the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum.

Near the back of the Citadel grounds we found the restored remains of Umayyad Palace. The Byzantine-style residence would have been the home and workplace of the governor of Amman. Despite falling victim to a strong earthquake in 749, the palace continued to be inhabited well into the 12th century, although it was never fully restored.

As one of the highest points in the city, the views at sunset were stunning. Flocks of black and white birds darted across the sky in swarms. The bustle of the city during rush hour dulled to a quiet hum.

We made our way back down to the city center, ready for dinner. When we travel, we favor local places with local cuisine and Hashem was exactly what we needed.

From the street, the 50-plus-year-old family-owned restaurant appears to be a few tables, in an alleyway. On our first visit, we took one of the tables near the sidewalk near a group of tourists, but on our second visit (yes, we went twice), we continued down the alley and through the kitchen to a larger dining area filled with locals.

Here the spirit of Hashem truly shined. The waiters hustled with trays full of food and water glasses, their feet slipping on the tile floor, but never spilling a drop. The food is vegetarian. There is no menu and no ordering unless you want mint tea… which you do.

The waiter brings out a plate of raw onion, tomatoes and mint along with a large piece of flat bread. Soon, a plate of falafel, french fries, seasoned fava beans (ful medames) and hummus mixed with yogurt arrive at the table. The falafel is considered the best in Amman and I’m not going to argue.

After dinner, we saw a line. If we’ve learned anything in our travels, it’s “if you see a line, get in it.” This particular line led to the tiny pastry shop Habibah. Opened in 1951 in an alleyway next to a bank, the shop cranks out plate after plate of kunafa. The queue leads to a small booth outside where we placed our order with the cashier—”one of each, please,” not entirely sure what we were getting.

From there, we took our receipt into the narrow shop with just enough room for two people to squeeze past each other. The kunafa—a mild white cheese melted under shredded wheat and covered in sugar syrup—was chopped, flipped on a paper plate and slid across the counter toward us. We shimmied past the queue and joined the others outside to enjoy our warm, sweet-and-savory dessert.

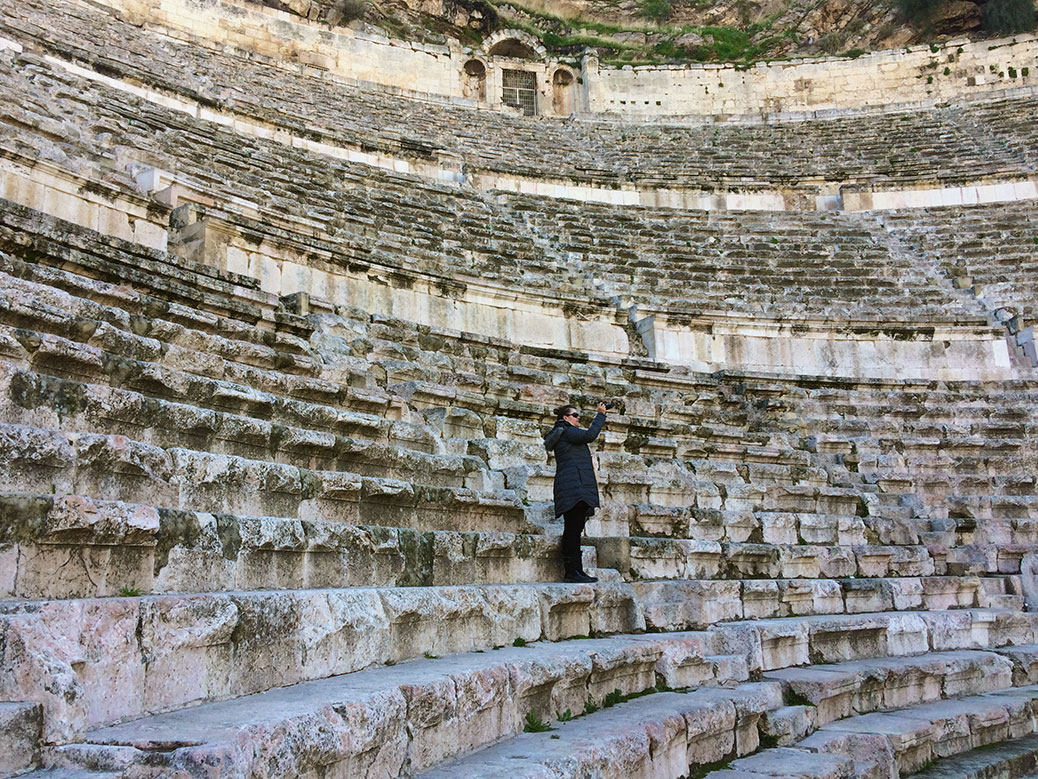

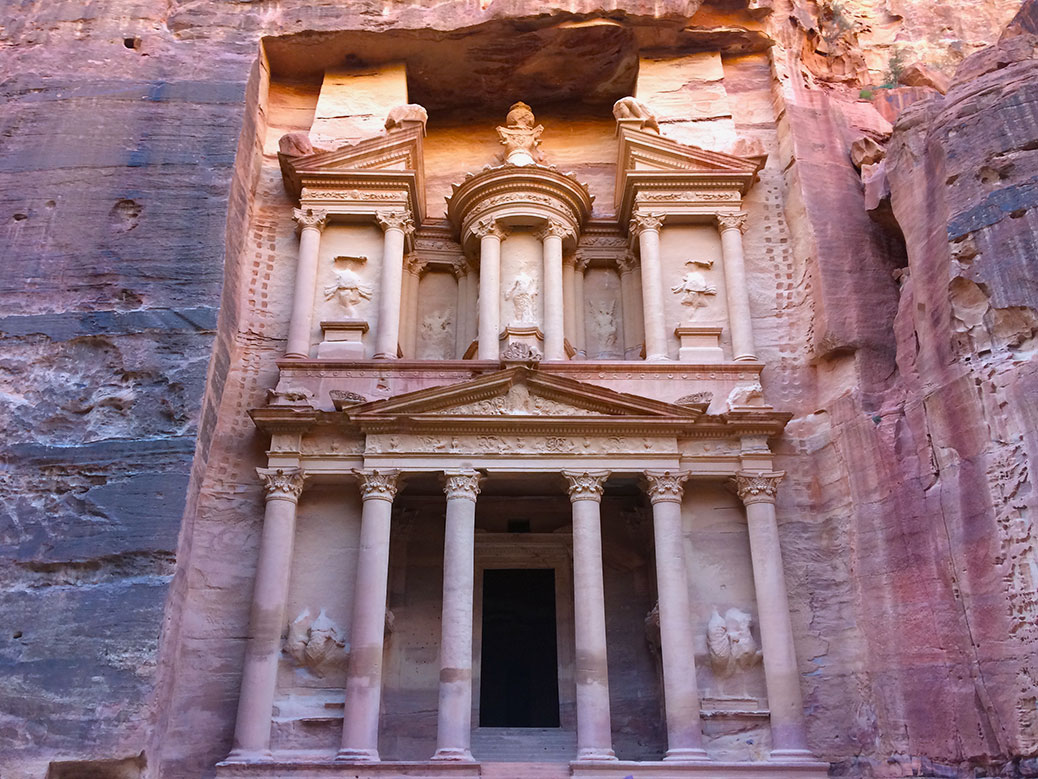

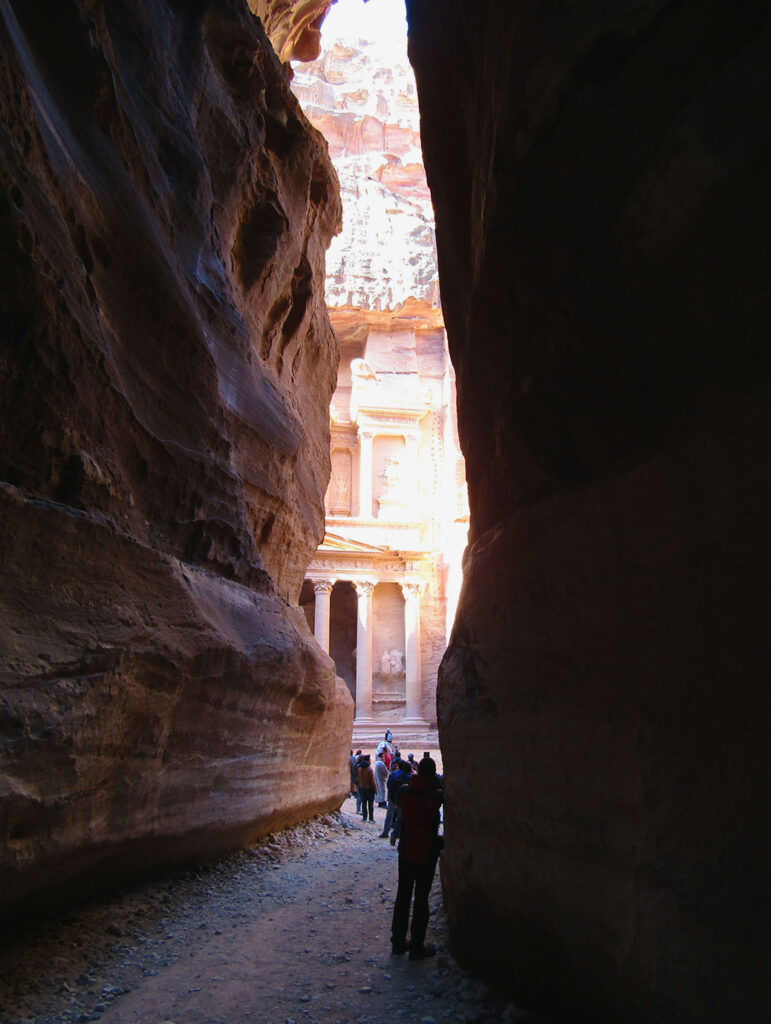

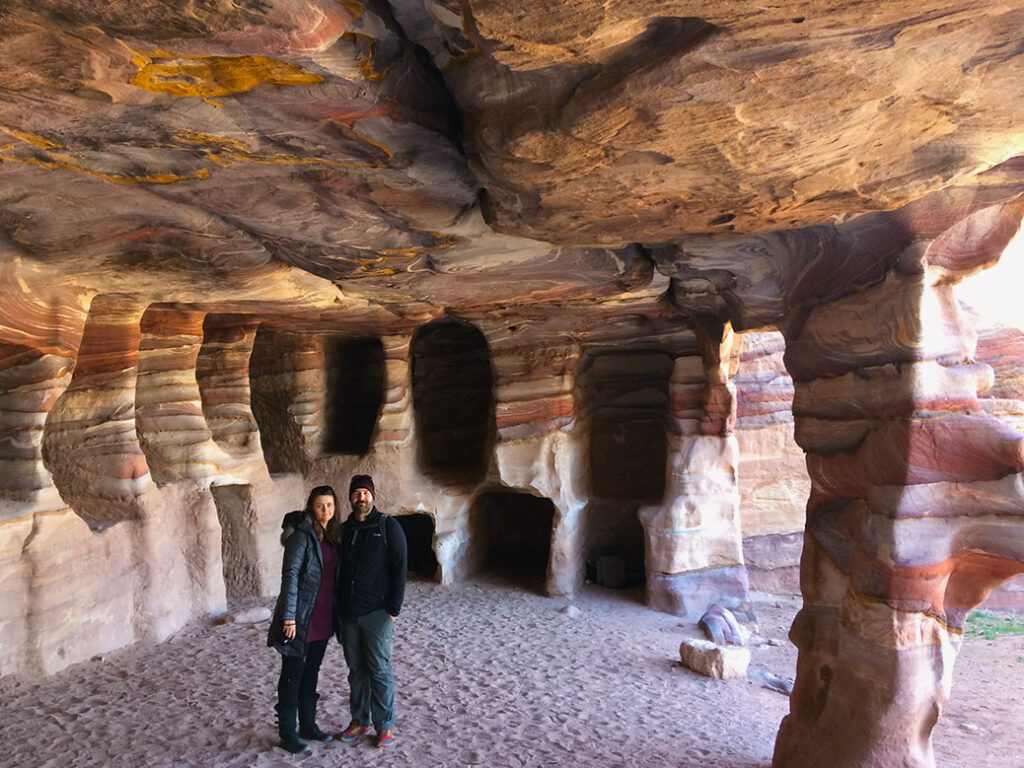

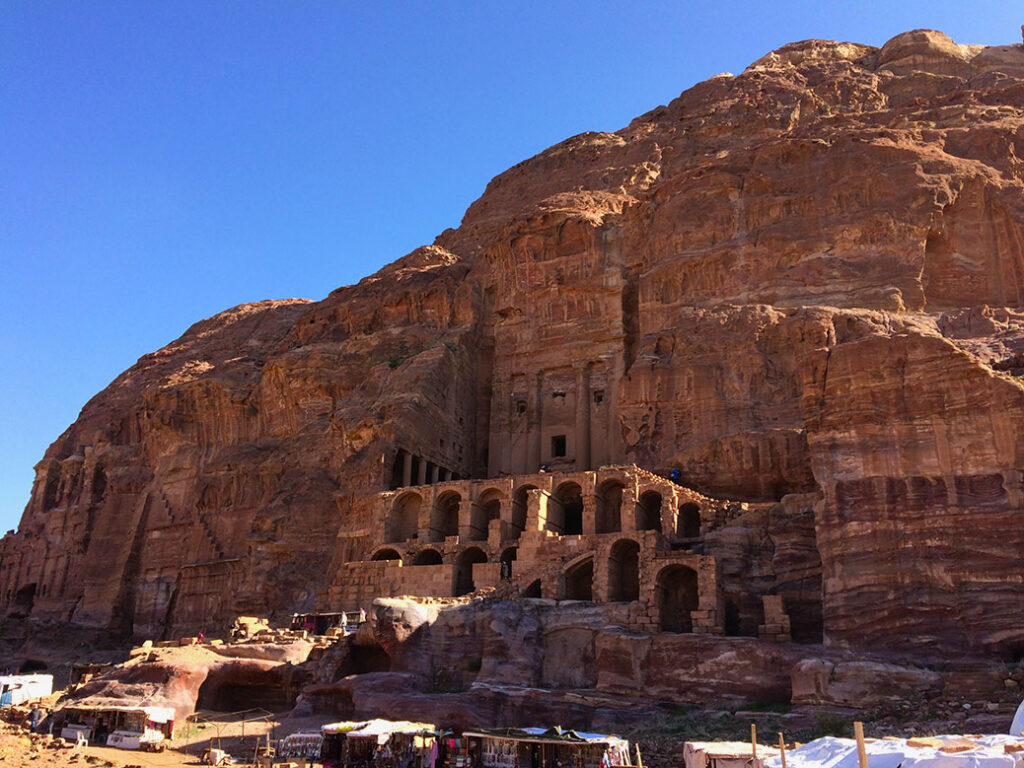

The following morning before we departed for Petra (check out our post on the Seven Wonders of the World), we grabbed a cup of Turkish coffee and walked over to the Roman Theater. The 6,000-seat theater was built during the 2nd century reign of Roman emperor Antoninus Pius. It still serves as Amman’s living room, hosting concerts and community events on a regular basis.

We returned to Amman after our Petra tour with a few hours to pass before leaving for the airport. After lunch at Hashem and another stop at Habibah, we wandered the streets, popping into the occasional shop and enjoying our last hours in Amman.

A man with a table full of colored sand set up shop along the sidewalk. He motioned us over, picked up an empty glass jar and dumped some yellow sand in the bottom. He picked up a metal funnel and began to pour various colored sand into the jar. The funnel went up, the funnel went down. A black streak suddenly became the silhouette of a camel. Blue sand became a desert oasis. Orange sand turned into a sunset. All the while, he spun the jar around, creating mirror images on each side.

As he finished he paused momentarily, at which point I expected the sales pitch. Instead, he picked up another jar and began again. He thanked us for our time, we returned the thanks and continued our journey. It was the perfect end to our time in Jordan; a reflection of the hospitality and low-key vibe we experienced during our stay.

If You Go

Art Hotel

32 King Faisal Street — Simple, clean hotel in the heart of downtown Amman. Buffet breakfast included. The staff is wonderful and the manager, Sameer, helped us with car transfers both before our stay and when we had trouble getting back to the airport days after we’d checked out.

Hashem Restaurant

Al-Malek Faisal Street — The best falafel in Jordan. Head toward the back to dine with the locals and try the mint tea.

Habibah Sweets

Al Hazar Street 2 — You can find a few Habibah locations, but this is the original. Ask for one of each of whatever kunafa they happen to be serving.