No matter where you are in the world, the topic of weather is a popular one. Everyone has an opinion on the weather, so it’s a perfect conversation topic amongst strangers. We all plan our activities and clothing choices around the weather. One of the first things our various Japanese language lessons teach is how to say “It’s good weather today, isn’t it?” (今日は良い天気ですね).

Meteorologists are regular targets of death threats and harassment when their forecasts go awry. The forecast is so important in South Africa that independent forecasters can be fined or imprisoned for incorrectly predicting the weather.

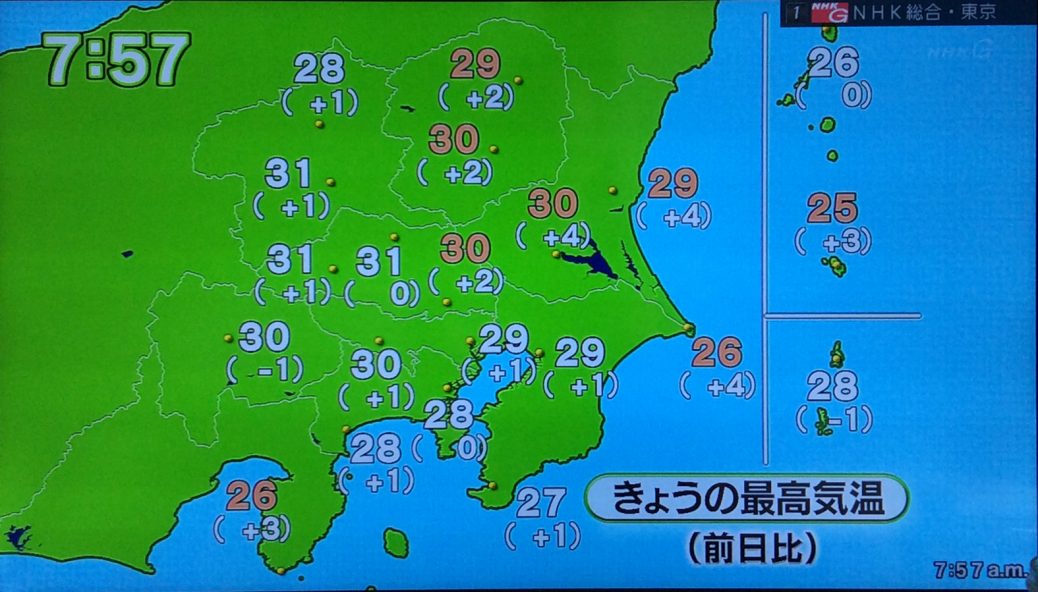

In Japan, a country whose citizens spend a significant amount of time navigating the day on foot or bicycle, the weather report is a big part of the morning newscast. From your run-of-the-mill temperature forecast to predicting the path of wild weather from Pacific typhoons, the forecast covers it all.

The wind and tides forecast is part of our daily weather story. In addition to damaging storms, the daily breeze can help determine whether it’s a good day to wash blankets (and hang them outside to dry), air out the house (high winds bring in a lot of dust and dirt) or bring a light jacket despite warm weather. Fire danger is a big concern in Japan and the prevailing winds can alleviate or amplify those worries. The forecast is important to coastal fishermen as well.

Then it gets fun. There’s a daily laundry forecast. Most Japanese homes don’t have clothes dryers (we don’t). Laundry is hung out on poles mounted over patios or outside apartment building windows using a variety of strategic drying gadgets. The scale goes from blue (hard to dry) to orange (dry well) depending on the day’s weather conditions. Today is a good day to do laundry.

The ultraviolet rays forecast shows the strength of UV rays throughout the day. Many women wear large, floppy hats, arm-length gloves and carry a parasol to protect themselves from the harmful rays of the sun. I wish I’d seen yesterday’s forecast before my run. My shoulders were Barney the Dinosaur purple!

Finally, the heat stroke index. At first, I thought maybe this was the child tolerance index—how long your child will last before having a meltdown due to the heat. This one ranges from safe (ほぼ安心) up to danger (危険). Today in Saitama (さいたま), we’re in the caution (注意) to vigilance (警戒) range. All jokes aside, it gets hot and humid in Japan during the summertime. In 2013, nearly 40,000 people were hospitalized from June to August due to heat stroke and 78 people died from complications.

Best of all, the weather forecast leads into the morning 15-minute soap opera miniseries. The current iteration—NHK’s 92nd asadora or morning drama series—is about a young woman who moves to Yokohama to become a baker, but finds that the cake just doesn’t taste right and sets out to create the perfect pastries. The previous miniseries featured Charlotte Kate Fox, NHK’s first American actress in a leading role, about the creation of the Nikka Whisky Distilling company.