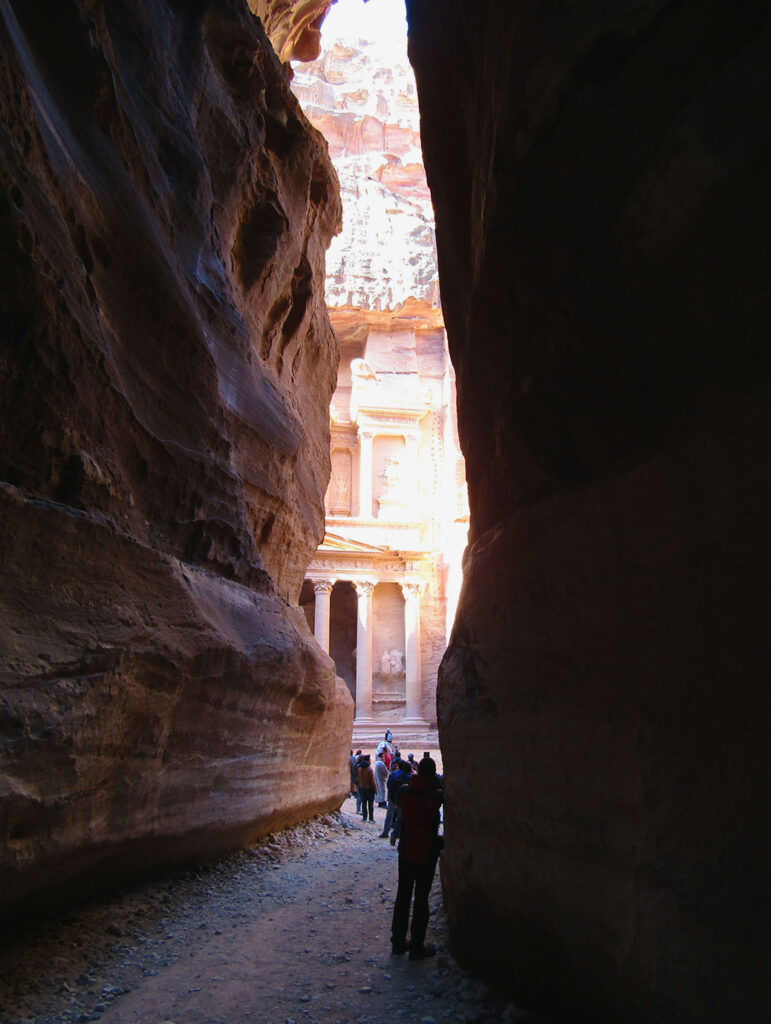

Westerners have a long tradition of discovering things that were never lost in the first place. The ancient city of Petra, hidden away in Jordan’s southwestern desert, was “discovered” by Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812. However, the Rose City—named for the color of the sandstone in late afternoon—had long been an object of curiosity in the region.

Today, Petra is one of the New Seven Wonders of the World (check out our rundown of the Seven Wonders we’ve visited) and Jordan’s most popular tourist destination. But 2,000 years ago, it was the capital city for the nomadic Nabataean people. They lived in caves chiseled deep into the sandstone and carved intricate facades into the outer walls to indicate temples and tombs.

After driving from Amman the night before, we started our visit early to beat the rush of tourists. Upon entering Petra, signs of ancient life are immediately visible. Shapes in the sandstone are easily identified as man-made, despite nature’s attempts at reclamation.

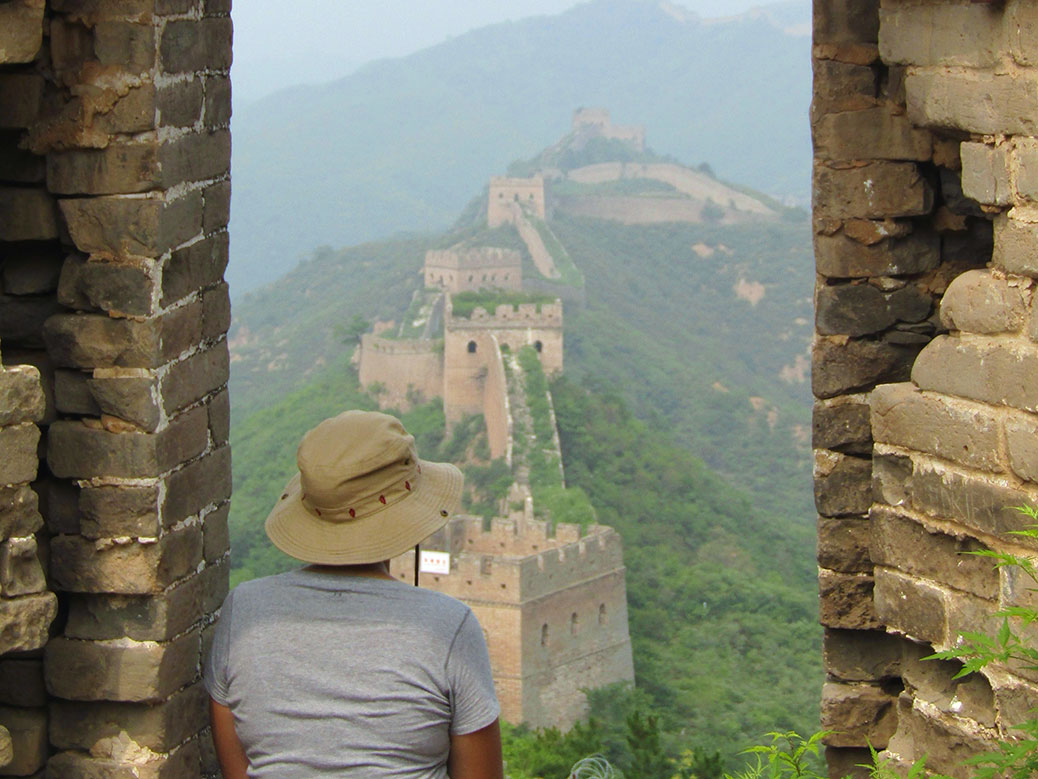

Before long, we arrived at a crack in the earth. The Siq, a natural passageway formed by a prehistoric earthquake, is as narrow as 10 feet wide and as tall as 600 feet. The sandstone canyon stretches more than a kilometer. It’s a walk through natural history with millions of years of layered sediment painting the walls. As the sun moves through the sky, the colors change from gold to rose.

In stretches, we also walked atop human history. Cobblestone roads installed by the Roman Empire during the 1st century AD are still visible. Remnants of 2,000 year old clay irrigation pipes line the sides of the wall, once providing water to the city.

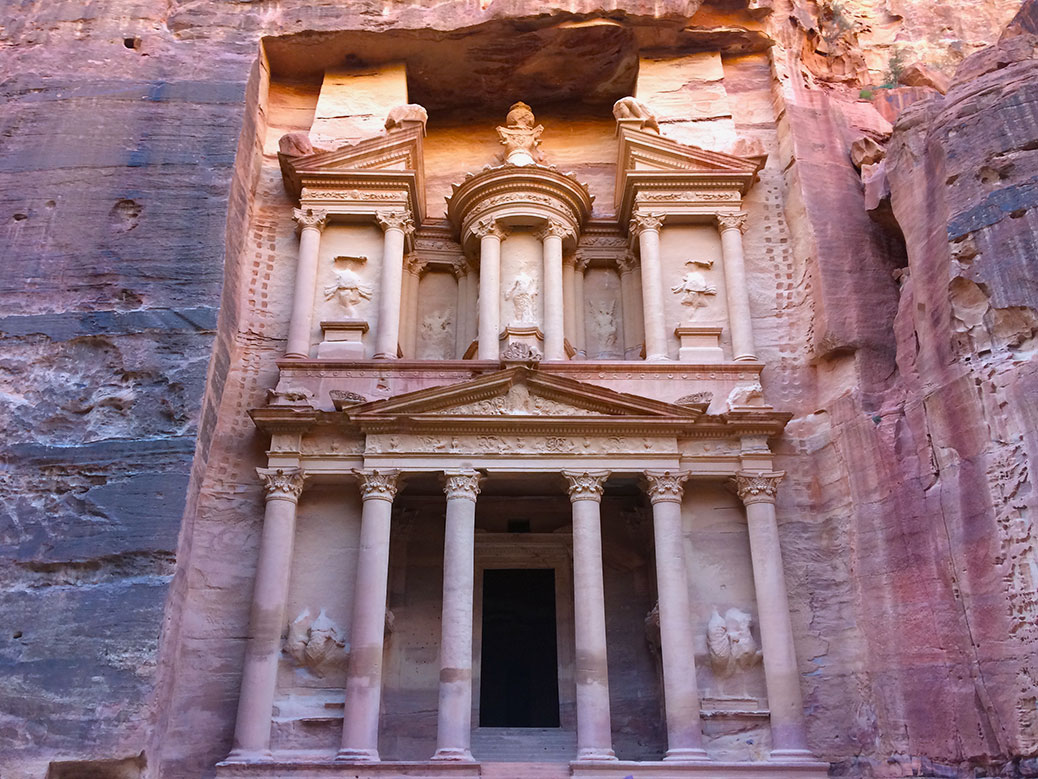

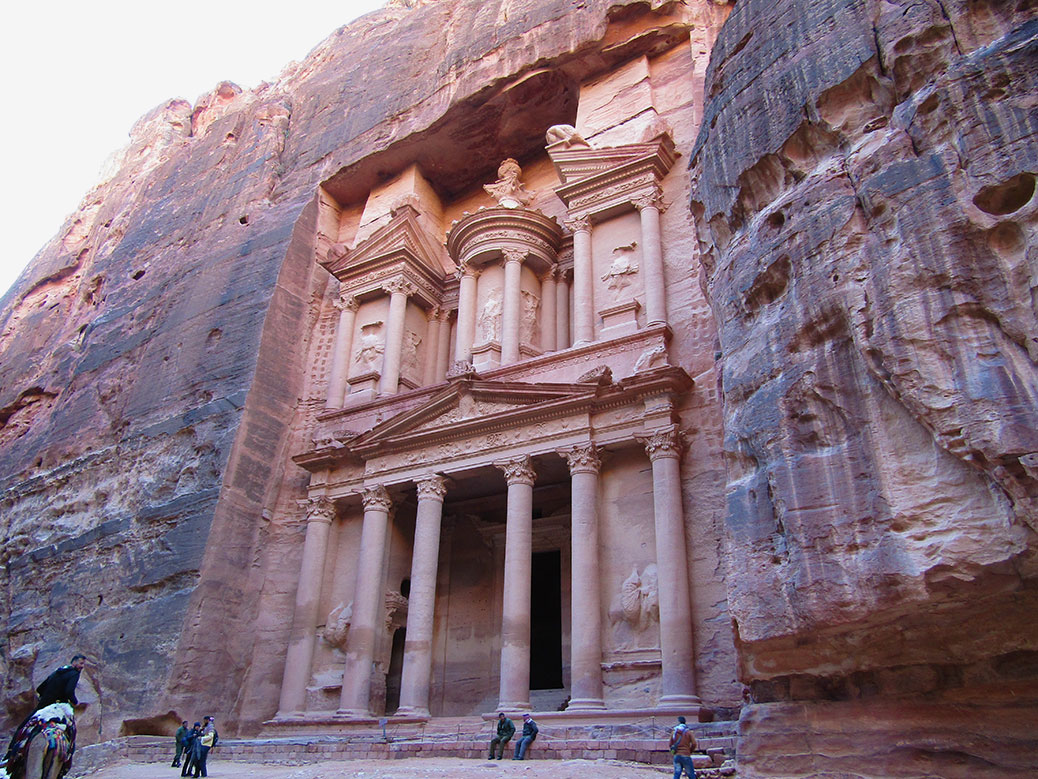

The Treasury

As we approached the end of the Siq, we caught our first view of the main event. Al-Khazneh—better known as The Treasury—is Petra’s most famous building. Carved around the same time as the arrival of the Romans, its architecture is a mix of Nabataean and Greek Hellenistic influences. It began life as a mausoleum, but earned its nickname due to a local legend that the urn carved above the second floor contained gold. Bullet holes are still visible where local Bedouin tribes tried to shoot the gold free from its perch.

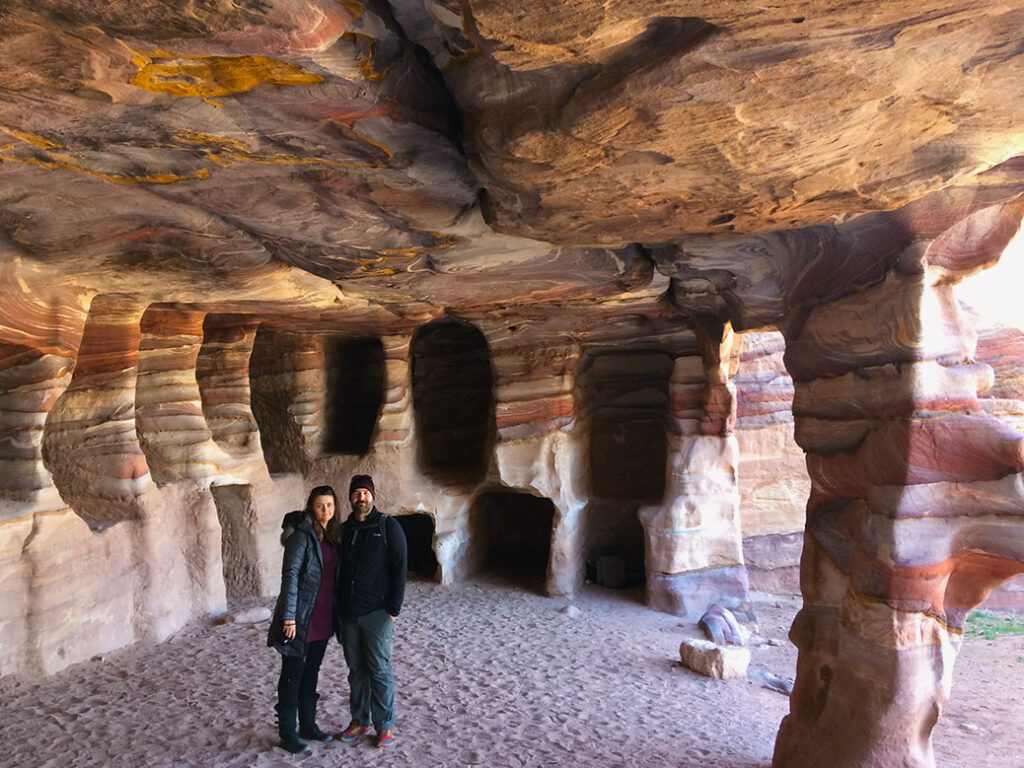

Continuing from the Treasury, we found ourselves entering the Street of Facades. The street is marked with tombs and false fronts framed by ornate facades. Instead of following the tour groups into the old city center, our fantastic local guide led us against the side of Al Kubtha Mountain. From here, we could peer into former tombs of the local people. Not unlike the carved caves that housed them, tombs were dug into the floors and walls.

The caves are the best place to get up close and personal with the history of Petra. Wall carvings from the people who have lived here over the past two millennia are still visible. We marveled at the natural artwork created by the layers of wind-swirled sand. Spectrums of reds, yellows, purples and earthtones provided decoration for living quarters and final resting places alike.

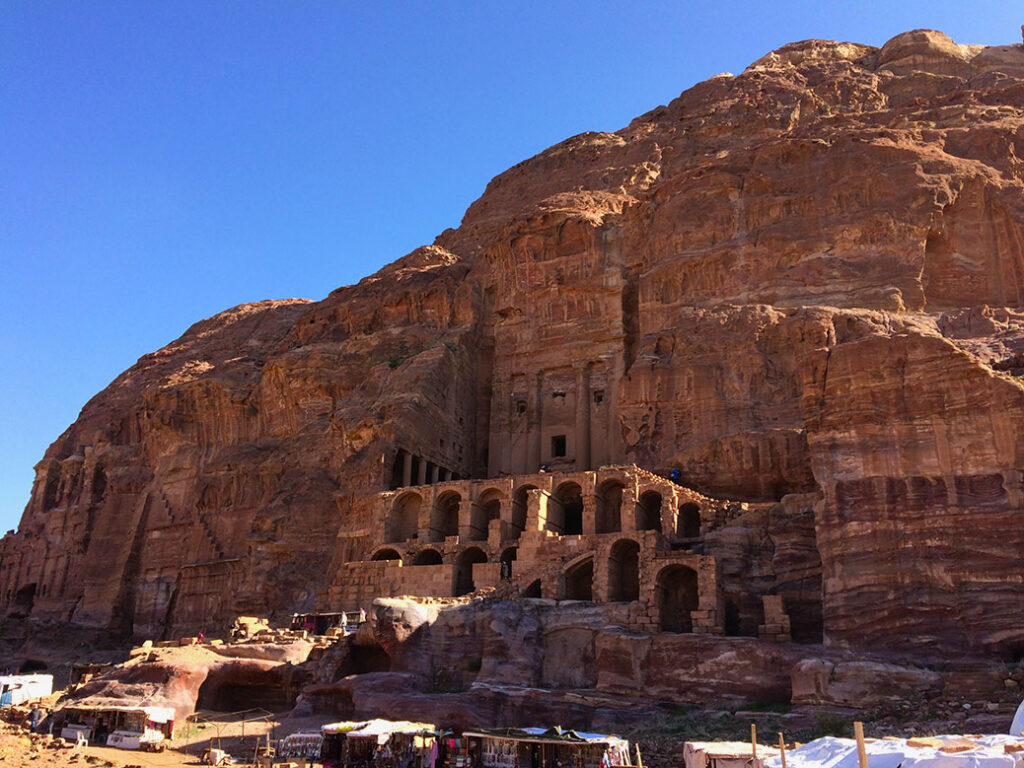

The Royal Tombs

Our guide led us around the corner where we came upon another set of buildings. Four Royal Tombs wrap around the northeastern end of Al Kubtha Mountain. The first is the Urn Tomb. With more depth than the previous facades, it was built for a Nabataean king—either Aretas IV or Malichus II—in the 1st century AD. Inside, inscriptions and asps designate the tomb’s conversion to a Catholic cathedral in the 5th century.

Nearby, the Silk Tomb, named for its richly-colored facade, slowly fades back into the sandstone. The neighboring Corinthian Tomb provides another example of Roman architectural influence with its embellished column design. The Palace Tomb sits attached, three-stories tall with a large stage in front. It’s facade is inspired by the Golden House of Nero in Rome.

Top of the World

Our guide left us at this point with rough directions to the top of Al Kubtha Mountain. We climbed the long sandstone staircase to the top where we encountered a herd of mountain goats. With one eye on the goats, we made our way to the edge of the mountain where a Bedouin-style tent appeared.

Inside, a man named Salem offered free views of the Treasury and reasonably-priced refreshments. We sat on the edge of the stone, our feet dangling over the ledge, and enjoyed a Coca-Cola. Salem played a song on his traditional shepherd’s flute, served as official photographer and defied death while jumping between the levels of rocks along the sheer cliff.

The People of Petra

We began the descent back down the mountain, turning down the various offers of assistance from donkey wranglers. For the past two centuries, the nomadic B’doul tribe has called Petra home. Descendants of the Nabataean, the B’doul lived in Petra’s caves and—since the 1920s—made their living by selling goods, services and charisma to tourists.

In 1985, UNESCO named the landmark a World Heritage Site. In an effort to keep the tribe from disturbing the newly-arriving tourists, the Jordanian government relocated the B’doul to a planned community in the nearby hills overlooking Petra. Three decades later, the neighborhood is overcrowded and underserviced, yet few B’doul want to leave their ancestral home behind. Even today, many serve as watchmen, keeping an eye over Petra throughout the night.

Petra is a rare glimpse into the daily life of an ancient culture. From the amphitheater in the city center to the Roman Colonnade Street, history comes to life in this place. A 5th century Byzantine Church, discovered under the sand in the early 1990s, shows that Petra was still a lively civilization long after most historians thought it deserted.

Today, 85 percent of Petra still waits to be uncovered. What other secrets exist below the desert sand?