Our road to Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine started with empty stomachs.

It’d been months since we’d visited the gluttonous paradise of Loving Hut‘s vegetarian buffet. I loosened my belt, hopped on the train and headed for Tokyo’s Chiyoda ward. It’s hard to justify the nearly three-hour round trip just for lunch, so we figured we’d also check an item off our “to-see list” and hit up Yasukuni Shrine as well.

Lunch was even better than anticipated and I approached it with the vigor of a man facing his last meal. I was reminded of an early episode of The Simpsons, which also had a great joke about “fish bread” that sums up our typical eating-out experiences in Japan…

Yasukuni Shrine Flea Market

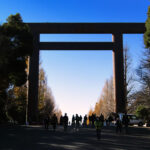

After the feast, it seemed prudent to walk the mile to Yasukuni Shrine. Approaching the main gate, we saw a couple tents set up selling used clothing. Then we noticed that the tents just kept going and going.

We’d lucked into the twice-a-month Yasukuni Shrine Flea Market. 150 vendors line the entry path to the shrine, hawking everything from the aforementioned clothes to pottery, books, toys and more. Secondhand goods are a rare find in Japan as it is, so stumbling upon a flea market is like finding gold at the end of a rainbow.

Click any photo in the gallery to see a larger version and start a slideshow view

The prices were also lucky for Tokyo standards, with nice pieces of tableware going for just 300 yen (about $2.50 USD). Viktoria scored a pair of boots for just 200 yen ($1.65) from a vendor who was also a terrible negotiator. The price started at 400 yen, but when we noted they were a bit too small, she lowered the price to 300 yen. When we pointed out a small pull in the zipper, she dropped it to 200 yen. My guess for her negative-negotiating fervor is the boots are cursed… only time will tell!

A Controversial Memorial

Yasukuni Shrine itself isn’t any more spectacular than any of the other major shrines in Tokyo, but its history is far more polarizing. Established in 1869, Yasukuni enshrines the spirits of those who died in battle while fighting for Japan. At present, nearly 2.5 million people have been deified in the shrine.

The official stated purpose of the shrine is as as memorial to those soldiers, relief workers and factory workers who supported various war efforts. However, critics view the shrine as a monument to Japan’s imperial military past. The first soldiers to be enshrined fought for Emperor Meiji in Japan’s civil war (Boshin War), which effectively ended the Edo Period and shogunate rule in Japan.

Yet, it was the post-World War II enshrinements that cast the shrine in its current controversial light. More than 5,700 Japanese military personnel were convicted of war crimes by international tribunals in the years following the war. Class A charges were levied against the leaders who planned and directed the war, most notably General Hideki Tōjō, Japan’s prime minister and the man responsible for the bombing of Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor in 1941. The remaining ranks were charged with Class B and C infractions for “conventional” crimes as well as crimes against humanity.

War criminals were initially excluded from enshrinement in any Japanese shrine. In 1954, the government began to loosen the restriction and Class B and C criminals were enshrined at Yasukuni over an 8-year period beginning in 1959.

In 1970, the shrine resolved to accept the Class A war criminals for enshrinement, a decision that mostly flew under the radar at the time. However, the residing priest postponed the enshrinements until after his death. In 1978, the Class A criminals were enshrined in a secret ceremony.

Japan’s wartime emperor Hirohito refused to visit the shrine after the enshrinement; a close advisor wrote that the emperor was “displeased” with the decision to include the Class A criminals. His son, the current Emperor Akihito (who incidentally celebrated his 82nd birthday yesterday), has never visited the shrine.

A simple visit to the shrine can put public figures under unwanted spotlight. An October visit by two mid-level Japanese cabinet members led to official condemnations from the governments of China and South Korea, two countries who suffered greatly at the hands of the Japanese during the war. China’s Foreign Ministry publicly criticized pop star Justin Bieber after he was photographed at the shrine during a 2014 visit.

In November, a bomb exploded in a shrine restroom during the annual autumn festival. The bomb was believed to be a politically-motivated response to the remilitarization of Japan’s armed forces—a purely-defensive organization since the end of WWII.

Erasing The Past?

As far as I know, the Chinese Foreign Ministry hasn’t publicly condemned our visit. The only real difference I noticed from any other shrine is that photographs were strictly forbidden. A solitary security guard waved off anyone attempting to photograph the shrine up close. The shrine’s website has strict rules about media coverage that apparently extends to the average visitor.

Click any photo in the gallery to see a larger version and start a slideshow view

Yūshūkan, a military museum located on the shrine’s grounds, doesn’t do much to help the image of glorifying the war era. A statue of a tokko pilot—better known as a kamikaze pilot—stands outside the musuem. An A6M “Zero” fighter plane, similar to the ones that attacked Pearl Harbor, is on display in the museum’s front room.

Yasukuni raises an interesting question about how to embrace the questionable parts of a country’s past. Is it right to ignore the souls of two million soldiers who were just following orders, no different than any other soldier of any other nation during any other war?

Japan, for its part, has spent much of the last 70 years apologizing, but the current government is starting to back off that policy, much to the outrage of China, Korea and others. Short of Japan fully falling on its sword over WWII atrocities—effectively committing modern-day political suicide—the conflict between these countries isn’t going anywhere.

Embracing Today

The sun shined brightly through the few orange and yellow leaves that remained on the barren winter maple trees in Yasukuni’s Shinchi Teien garden. War and controversy would be the furthest thing from anyone’s mind crossing the stone bridge over the garden’s pond.

Click any photo in the gallery to see a larger version and start a slideshow view

A young couple dressed in traditional Shinto wedding clothing payed their respects at Yasukuni’s alter. Young archers practiced in the distance behind the shrine’s sumo arena, home to the annual spring wrestling tournament. The Nōgakudo stage was empty, but is often filled with traditional Noh plays and dance performances. The lively flea market began to quiet as vendors packed up their wares.

I don’t know the right answer for Yasukuni. The families of Chinese and Korean citizens who suffered during World War II have a right to be upset by the “glorification” of war criminals. Japanese who lost family members on the battlefield of not just WWII, but countless other wars, have a right to be upset that their loved ones aren’t allowed to rest in peace. Americans who lost loved ones at Pearl Harbor would be justified in cringing at the monuments to those responsible for taking their lives.

Maybe the right answer is that there isn’t one. To move forward, someone will have to be willing to leave the past behind. It will take the strength of nations, which is a lot to ask in this day and age.